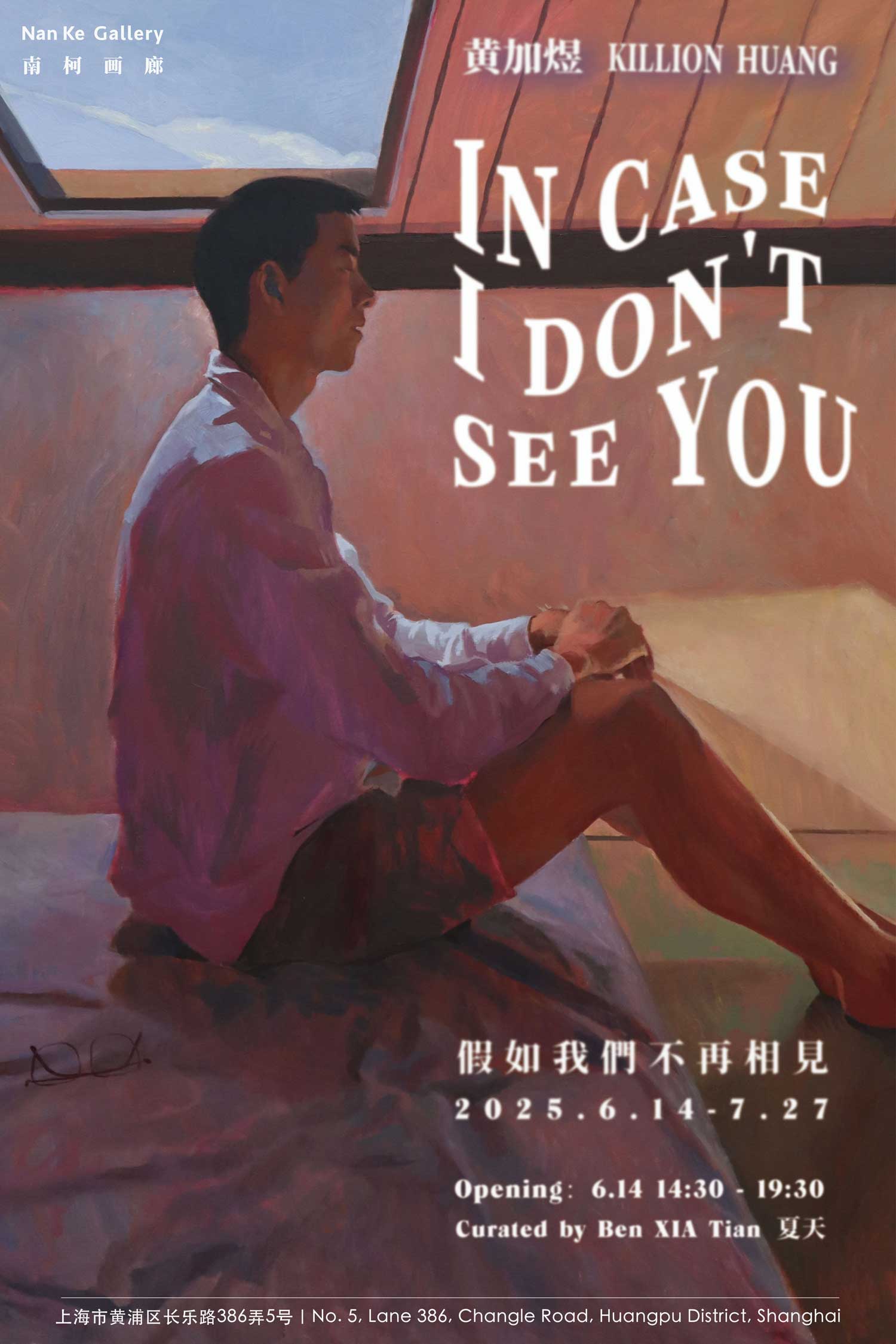

Nan Ke Gallery is pleased to present Killion Huang's solo exhibition, In Case I Don’t See You, opening on June 14. Killion's works employ emotive color as their primary language, depicting the postures of friends and sheltered interior spaces. His paintings—warm, intimate, and imbued with mutual trust—serve as "gifts" exchanged between the artist and his subjects. Viewers will discover tenderness in his brushstrokes, capturing the duality of day and night, queer domesticity, and intimacy.

Killion treats the interiors inhabited by his figures as extensions of his studio, with compositional choices reflecting careful observation. In framing and atmosphere, these works share an aesthetic principle with postwar queer photography by German artist Herbert Tobias: an allure born of self-containment. Rose pink often serves as the foundational tone in Killion's paintings, deliberately left visible on the canvas like an emotional substrate.

As someone with color vision deficiency, Killion perceives red, brown, and blue with heightened sensitivity. This divergence doesn’t hinder but instead forges his distinctive chromatic system—one that pushes subjective color perception to its limits while retaining recognizable realism. The artist admits that without red, his paintings would feel "too gray," revealing how these hues provide psychological security. The intense red-brown palettes, which might appear overwhelming to some, function as his visual tether to the external world.

In Killion's work, interiors transcend physical settings; they are planes of color where figures exist. Seagull Parisian (2025) exemplifies this: a skylit attic scene positions the subject at the intersection of four color fields, with blues and greens from bedsheets and floors echoing across walls. A yellow glow on the right edge repeats as linear highlights along the figure’s leg. Here, space becomes a double metaphor—the figure’s reliance on their environment, and the quiet radiance transmitted through pigment.

Chessboard Coastline (2025) sharpens this approach, with emphatic rectangular forms and defined edges mirroring the orderliness of Belgian interiors. Two figures lean against planar surfaces, while a curvilinear metal desk lamp—its powdery pink shade softening the composition—ties together the tablecloth and shadowed chair into a chromatic continuum.

Killion's focus on the body began during his apprenticeship, when he abandoned sterile life-drawing for the natural fall of light on skin. This shift revealed his preference for human connections over landscapes. The exhibition’s interiors—a disciplined Belgian home, a cramped Shanghai apartment, a sunlit Thai hotel—act as thermometers for emotional temperature. Killion often compresses ceiling space, directing attention to figures encircled by objects. Faces are blurred or simplified to emphasize the honesty of posture, as seen in Folding Fan (2025), where a slender woman’s tense thumbs and curled toes contrast with the room’s languid brushwork. Yet across most of the canvas — in the luminous, cloud-like floor, the verdant mountain backdrop, and the wood-grained storage cabinet — unfettered brushwork dissolves the figures' restrained emotions.

The triptych Urd, Verdandi, Skuld (2025) takes its title and theme from the three Norns of Norse mythology—goddesses who represent time and fate: the past, the present, and the future. They also serve as a metaphor for encounters, coexistence, and separation between individuals. Our destinies are interwoven in fleeting moments, only to eventually drift apart. In the painting, the three standing male figures appear nearly identical, yet the temporality implied by the mythic motif is subtly embedded in the shifting temperature of light—moving from cool to warm. Huang Jiayu uses this nuanced control of color to evoke the passage of time and the unfolding of fate. Such delicate sensibility is characteristic of much of Huang’s work, where the flow of time quietly stirs emotional resonance in the viewer, particularly in relation to human connection.

As a young artist, Killion openly engages with art history: Pierre Bonnard’s flickering interiors, Jamie Wyeth’s melancholy portraits, David Hockney’s spatial choreography, and the joyous figuration of his mentor T.M. Davy. New experiments like Cave Dive (2025) plunge figures deeper into architectural space, exploring artificial light and materiality to interrogate identity within complex systems.

Through rose-tinted anonymity, glowing contours, and pliant textures, Killion invites viewers into a boundary of intimacy. His works—nesting queer yearning within protective interiors—propose a defiant wholeness against societal exclusion. The title In Case I Don’t See You, borrowed from The Truman Show, nods not to farewells but to the preciousness of connection. These paintings extend an invitation: to traverse the artist’s memories and arrive at universal desires—for beauty, and for love.